Two Opposite Approaches to Building a Fragrance Portfolio

Should brands try to cover a broad range of olfactive profiles or focus on a small niche? How can they avoid repetition while still maintaining their brand DNA? Let’s dig into it.

When planning out the composition of a fragrance line, brands start noticing an interesting paradox: consumers don’t like it when brands “repeat themselves”; yet they have very specific olfactory expectations from each brand and don’t like it when these are not met in new launches.

So, they end up facing a difficult problem: how to find that elusive “something” that allows for a diversity of genres and olfactive profiles, yet holds the brand together and gives it a distinctive signature, a so called “brand DNA”? But also: how to select the theme and olfactive direction for the next fragrance release? Should they prioritize diversity of products for broader market coverage, or should they respect the preferences of brand’s core customers and keep it more narrow? Our stance on this: you can do either if it aligns with your strategy, but it should be done differently than it often is.

What happens now when new brands want to cover different tastes and preferences is that they often compose a line with one amber/gourmand, one fresh citrusy fragrance, one rose-centered fragrance, one musk or iris, etc. This strategy is reminiscent of film studios producing TV shows that include at least one key character for each demographic and at least one episode for each of the current socio-cultural trends to ensure all micro-segments of the market are covered. This makes them appear perceivably targeted, calculated, predictable, and lacking the magic of more eclectic TV content from prior decades. This is where many niche fragrance brands are headed as well, and this is what makes them seem less niche and more commercial.

There is nothing wrong with exploring different genres or key notes as you build the line. After all, we should consider consumers’ strong fixation on notes and genres in the discovery phase. However, there is a benefit in doing it in a less blunt manner, leaving an impression that there is too much going on in each fragrance to call them just a “rose scent” or an “iris scent”. (Note: you will rarely find this focus on notes in the product lines of more established luxury brands).

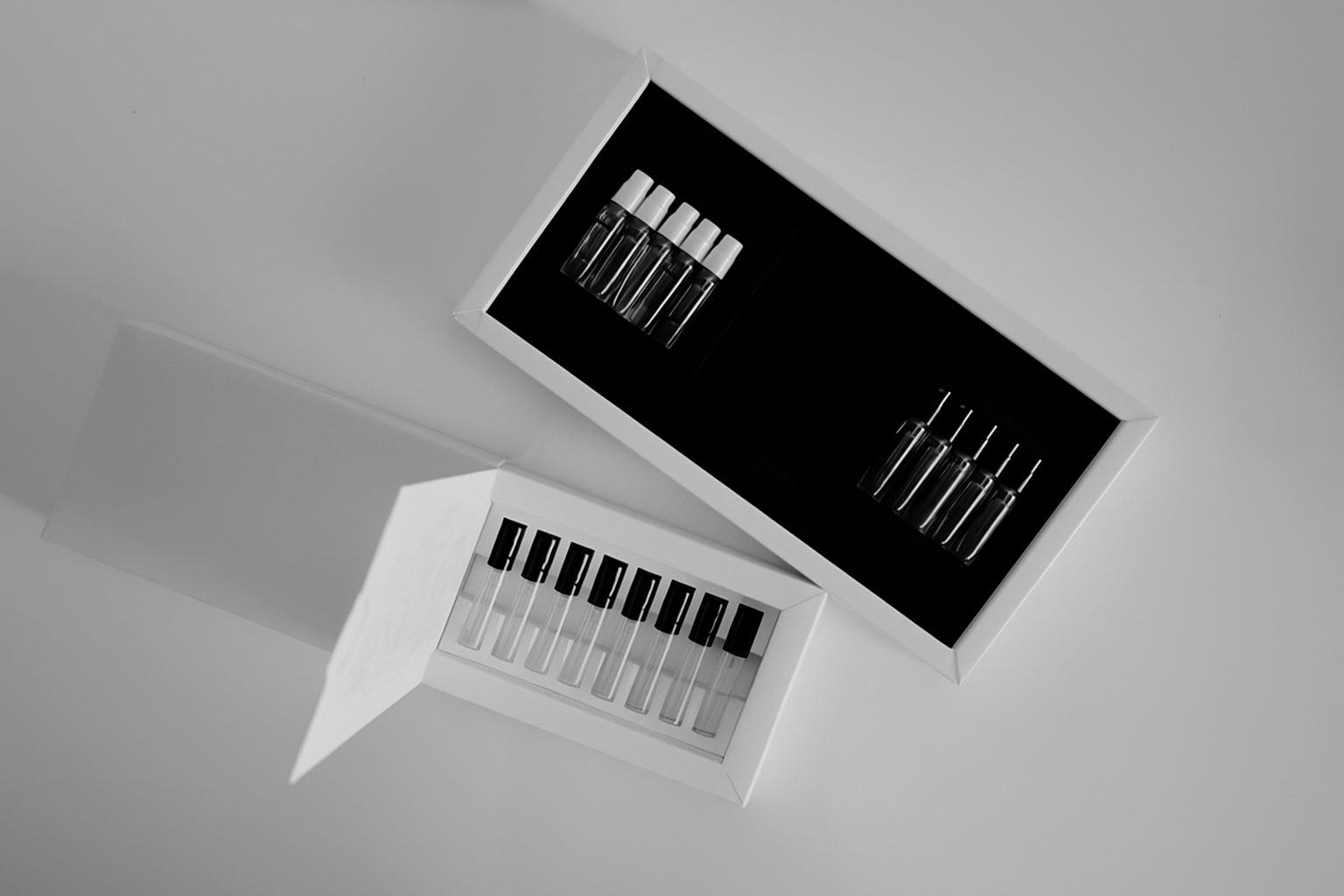

Now, let’s talk about another extreme – focusing the entire line on one micro-genre or one key accord that repeats from fragrance to fragrance. Normally, this won’t be well received: flankers are very common in the mass market and luxury segments, but aren’t really a thing in the niche segment. However… (shhh – here comes a real business idea) it may work well if presented to consumer as a concept in itself. For example, by promoting the idea of a “signature fragrance”. A line with a few similar smelling fragrances would allow the wearer to obtain a recognizable signature smell, while still offering a lot of versatility. This could be emphasized by promoting a non-traditional way of applying fragrances on clothes: we all know how hard it is to use different fragrances after applying a strong one that lasts for days or weeks on a scarf or outerwear – a line like this would solve this problem, as the residual smell wouldn’t interfere with the newly applied fragrances. A few big caveats here:

1) this concept would only work for super niche brands without a big ambition for expansion, unless we are talking about a small line under the main brand or a few mini-lines with similarly-smelling fragrances;

2) this would work best for consumers with a bit of a utilitarian approach – those who wear fragrances as a fashion item that enhances their image and refer to their fragrance collection as a “wardrobe”.